Ready for lift-off? A commitment to restrain anti-satellite weapons testing

Published in The Ploughshares Monitor Volume 43 Issue 4 Winter 2022

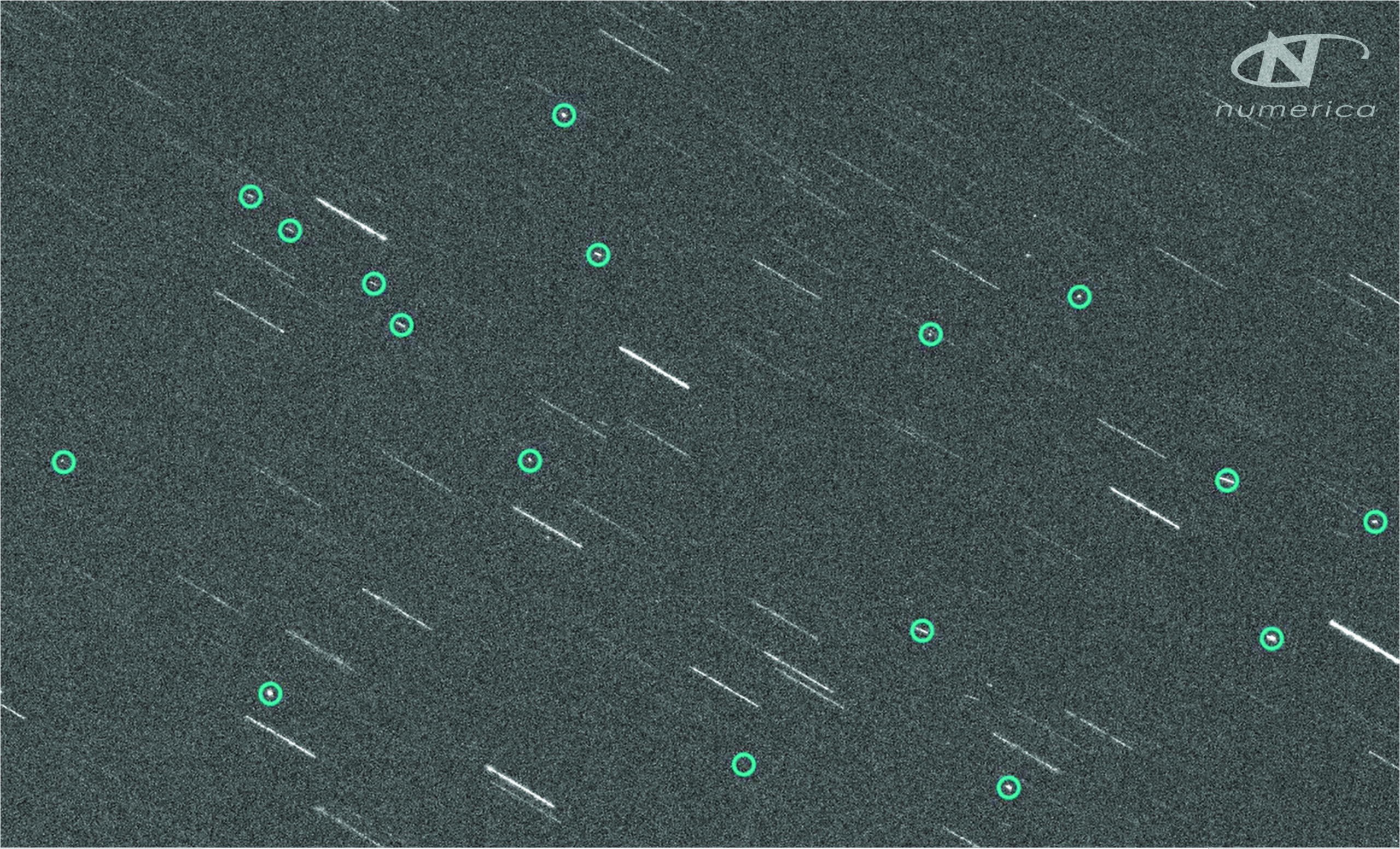

Awareness of the damaging effects of anti-satellite (ASAT) missile tests is growing. The most recent test, conducted by Russia in 2021, produced a cloud of space debris that forced astronauts on the International Space Station to take shelter in lifeboats. Today, the remaining debris continues to menace satellites and humans in space.

And now, political action is building. For the first time in decades, a concrete step is being taken to restrict the testing of such weapons, with the initiation of a new moratorium led by the United States.

Of course, this is but one step of the many that are urgently needed to preserve outer space for peaceful uses and dampen the drumbeats of warfighting in space. And political hurdles to widespread adoption remain. Still, after more than four decades of inaction, all such steps are valuable and to be celebrated.

THE NEED FOR STRONGER NORMS

To date, China, the United States, India, and Russia have conducted destructive tests of ASAT weapons, using their own dead or obsolete satellites as targets. These tests have been normalized and accepted by other states, as long as they don’t create “long-lasting” debris – a term open to wide interpretation.

But all debris from an ASAT test causes harm. And all destructive activity in space creates debris. If such tests continue, the resulting debris could become an indiscriminate hazard to astronauts and satellites, negatively impacting our ability to use outer space for generations. These tests also contribute to the political dynamics of arms racing, encouraging other states to join in.

Walking back this norm is not easy but it is necessary.

This past May, the first substantive meeting of the United Nations (UN) Open-Ended Working Group (OEWG) on Reducing Space Threats took place. The OEWG is tasked with developing additional norms of responsible behaviour to mitigate threats to space systems, and considering how such rules might contribute to future negotiation of a legally binding agreement. Space debris is an obvious threat to tackle; not only does it create a persistent and indiscriminate threat, but almost all of the more than 30 national submissions sent to the UN Secretary-General during initial consultations mentioned debris.

MOMENTUM FOR MORATORIUM BUILDS

On April 22, the United States announced a unilateral moratorium on destructive testing of ground-based, direct-ascent anti-satellite missiles; it would not ban the development or possession of such capabilities, most of which are embedded in anti-ballistic missile defence systems. The focus on destructive testing means that accessing technology, developing ASAT capabilities, and conducting non-destructive flight tests are not restricted.

Momentum for a global moratorium is growing. First joined by Canada and then by New Zealand, Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom, South Korea, Switzerland, and Australia, the United States is now pursuing a UN resolution that calls upon all states to commit not to conduct destructive direct-ascent anti-satellite missile tests.

Nonetheless, this pledge by the United States complements and strengthens existing international commitments to mitigate the production of space debris, including UN guidelines on the long-term sustainability of outer space activities, while taking aim at a particular use of a weapons capability.

Such a strict test ban is also a strong arms control tool because it provides a clear and specific commitment that is easy for others to understand and to monitor for compliance, using widely accessible tools such as space situational awareness data, which are available from both state and commercial providers. The practical success that the moratorium affords can support subsequent initiatives that are wider in scope, while dampening a driver of arms racing and insecurity.

Momentum for a global moratorium is growing. First joined by Canada and then by New Zealand, Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom, South Korea, Switzerland, and Australia, the United States is now pursuing a UN resolution that calls upon all states to commit not to conduct destructive direct-ascent anti-satellite missile tests. As Canada noted, such an initiative could grow into a much desired legally binding agreement.

BUT OBSTACLES REMAIN

Russia, China, and India – all states with demonstrated ASAT missile capabilities – are not yet on board.

Both Russia and China claim that this moratorium, coming after states, including the United States, have demonstrated their own hit-to-kill capabilities in space, discriminates against states that don’t have ASAT weapons. China insists that the United States is not “giving anything up,” while Russia claims that “certain states won’t have a shield while others still have a sword.” Both states also claim that the moratorium is too narrow, leaving the door open to the development and even operationalization of ASAT missile capabilities, while not addressing potential weapons capabilities in outer space at all.

Meanwhile, citing adherence to previous debris mitigation commitments, India insists that its own test was a “responsible” action.

It’s likely that support for the moratorium will continue to grow, creating what Robin Dickey describes as “normentum.” But success in bringing as many states as possible on board will ultimately require an ability to cross political divides.

The fact that the moratorium narrowly takes aim at destructive tests of systems and not capabilities should help to dispel concerns about technology discrimination.

Concerns about asymmetric capabilities can also be eased. As with nuclear weapons, ASAT missiles have a limited use in combat, because no one, including the aggressor, can be protected from the destructive environmental effects of a strike. As well, the growing diversity and redundancy of space-based capabilities mean that the ability to strike at one or even a few satellites won’t necessarily debilitate a system capability. Because states with fewer space capabilities are most vulnerable to the testing of destructive weapons, they have an incentive to rein in such behaviour.

THINKING BIGGER

But increased political fragmentation of the space governance framework is still possible. To avoid such an outcome, we need to think bigger.

While the inherent threats created by destructive ASAT missile tests – both debris and arms racing – merit a moratorium, momentum on this initiative should also be used to expand the scope of security commitments related to outer space.

The narrative that the moratorium doesn’t adequately constrain the United States hinders adoption and may reinforce political divides. The pursuit of additional modes of self-restraint can help. These might include moratoria or commitments related to other types of tests or demonstrations, such as directed energy or on-orbit capabilities; as well as restrictions on the deployment of space-based anti-ballistic missile interceptors. To build confidence and trust, all commitments must be specific, unambiguous, and easy to observe or otherwise verify.

The point is not to hold one initiative hostage to others. As the United States admits, the moratorium is only one of many initiatives needed to improve outer space security. For this reason, ongoing meetings of the OEWG, where discussions address a wide range of threats to space systems and avenues for responsible behaviour, are extremely valuable.

We must also think beyond restraint. What is needed for space security to be realized is a range of new tools and mechanisms that allow better communication, consultation, information exchange, and data sharing.

Even without additional measures, this new U.S.-led moratorium is a win for both space sustainability and arms control. While more is needed, we should take a moment to appreciate the progress that has been made.

Photo: This telescope image shows debris from the Kosmos 1408 debris cloud shortly after destruction by impact with Russia’s A-235 “Nudol” anti-satellite weapon. The image was collected at 5:43:11 UTC on 15 November, 2021, shortly after destruction of the satellite. “Kosmos 1408 post impact debris” by Cam Key on behalf of Numerica Corporation is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0