Space governance at the breaking point?

Published in The Ploughshares Monitor Volume 40 Issue 3 Autumn 2019

More countries, companies, and people than ever before are becoming involved in space activities. By bringing in new excitement and enthusiasm, they are driving innovations on how we all use space to provide benefits on Earth to meet a wide variety of global challenges.

However, the challenges to space security and sustainability are also growing. If space governance is going to crack under the strain, it could do so sooner rather than later. Yet, all hope is not lost. The chorus of voices, of both state and nonstate actors, is getting louder, demanding that the space community stop merely talking about problems and start fixing them.

THE GROWTH IN SPACE ACTIVITY

Last year, at least 11 countries either announced that they would soon create national space agencies or actually did so. At least seven national space agencies were spending more than $1-billion a year. Several countries saw the first launch of their own satellite. Many countries are contributing more to the development of space applications, such as global navigation satellite systems and Earth remote sensing; several are also expanding into exploration and prestige missions. Particularly noteworthy is China’s outreach to other countries to participate in its upcoming Tiangong-3 space station, similar to what the United States and Russia did with their space stations.

The sheer number of objects launched in 2018 is astonishing. For the second straight year more than 400 payloads were launched into space: double the pace of previous years. The number of active satellites in orbit grew by roughly 20 per cent. Many of the new satellites were from commercial actors and illustrated the growing trend to small satellites and larger constellations. Although the really large communication constellations of hundreds or thousands of satellites have not yet started to launch, companies did begin to put up initial pathfinders and test satellites for them.

More countries than ever before focused on military uses of space and protecting their own capabilities. In 2018, 15 countries launched dedicated or dual-use military satellites. Several countries announced or continued plans to create dedicated military space organizations, policies, or strategies, recognizing that space capabilities are very likely to be a key part of future conflicts and need defending (or attacking). While operational deployment of destructive counterspace capabilities is still limited to a few countries, a growing number are developing, testing, or even using non-destructive counterspace capabilities, such as jamming or spoofing.

Space governance saw significant, if limited, progress in 2018. More countries than ever before were putting in place national regulatory and policy regimes, or modernizing and expanding existing regimes. The United States led the way, announcing a major effort to overhaul its existing licensing regime and the first-ever national policy to establish a space traffic management regime. Australia, Finland, New Zealand, Portugal, and the United Kingdom all announced new legislation to bolster their national licensing regimes.

Processes at the international level had mixed results. Several years of debate at the United Nations on guidelines to enhance the long-term sustainability of space activities achieved a major milestone. However, multilateral efforts on weaponization and space arms control continued to struggle. Informal discussions on a framework on using space resources continued to make progress, but formal discussions floundered because of ideological and geopolitical rifts.

A GAP IN SPACE GOVERNANCE

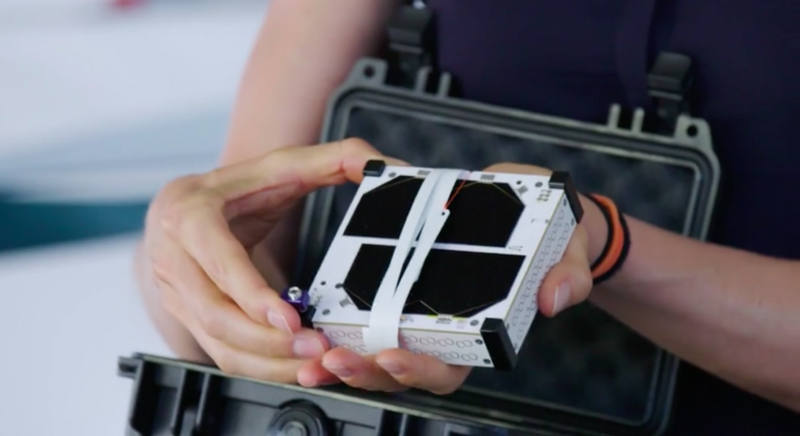

In 2018, Swam Technology launched its initial set of four tiny SpaceBees without a proper license. The U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) denied Swarm a license, citing the safety risk posed by the SpaceBees because they were too small to accurately track. However, the SpaceBees were launched anyway on an Indian rocket, in part because of the lack of effective communication between countries on responsibility for payloads that have multiple launching states.

Once on orbit, the SpaceBees were accurately tracked by both U.S. military and commercial radars. This result suggested that the FCC’s denial may not have been technically sound in the first place, and led to more questions about whether the FCC is the right organization to make such determinations on space safety.

This example shows some of the challenges for space governance. Commercial space activities are innovating and expanding too quickly for national regulatory regimes to keep up. Even the United States, which has the most comprehensive and robust licensing regime and the most capacity to deal with change, struggles to reform its existing policies, regulations, and licences to respond to the growing number and diversity of commercial space activities.

THE TIME FOR PRAGMATIC ACTION

In 2018, my colleagues at Secure World Foundation and I started to see a subtle shift in many of the space governance discussions we participated in or helped to facilitate. Across government, industry, academia, and civil society, we noticed more people going beyond expressing concern about the problem to making demands for action, and a small but growing cohort who started to take action.

Many of these actions were small in size or scope, but I would not belittle their potential impact. Small changes in big things can have huge impacts, particularly when those changes are incrementally ratcheted up over time. Small changes can also have lasting effects when they become established as new norms of behaviour and are reinforced by peer pressure and organizational culture.

Going forward, members of the space community must all work together to leverage this emerging demand for action to create a pragmatic plan to address the challenges to the space governance regime. As the first step in such a plan, we should identify the highest priority threats to space and the small, incremental changes in behaviour that can mitigate those threats. Actions already underway that meet this definition should be embraced and new actions started to fill in the gaps.

We should try to coordinate actions where it makes sense, but also realize that a large group of diverse stakeholders makes consensus difficult. A bottom-up approach rooted in technical expertise has been successful in the past and may help to mitigate conflicting interests and a lowest-common-denominator outcome. Multiple actions aimed at addressing the same topic may also be useful if they spark innovation and competition among different ideas and approaches.

Dr. Brian Weeden is the Director of Program Planning for Secure World Foundation and has nearly 20 years of professional experience in space operations and policy. This article is derived from the “Global Assessment” in Space Security Index 2019.

Photo: In 2018, Swam Technology launched its initial set of four tiny SpaceBees—one SpaceBee is pictured above—without a proper license. Swarm Technology