From Stockholm to Islamabad: Nuclear fears in a new tech environment

This spring I travelled from Stockholm, Sweden to Islamabad in Pakistan, from one conversation about nuclear risk to another.

At a Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) workshop on the space-nuclear nexus, we explored the growing nuclear risks that are linked to outer space and stem from the role of space systems in nuclear warning, command, and control; the growing unpredictability of conflict-escalation dynamics; and resurgent fears that nuclear-weapons capabilities will target space.

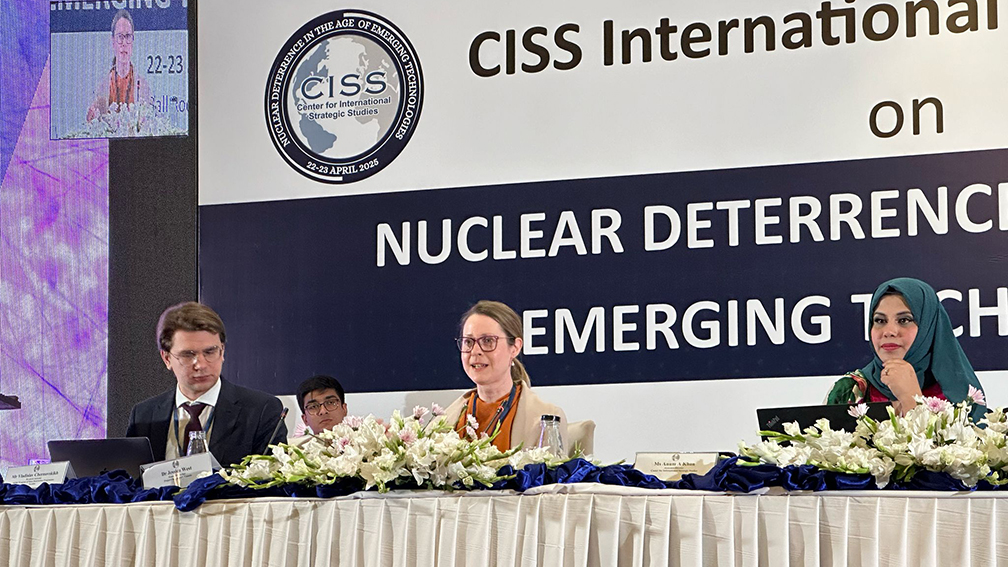

In Islamabad, at the international conference Nuclear Deterrence in the Age of Emerging Technologies conducted by the Center for International Strategic Studies, the focus shifted to the role of emerging technologies in reshaping the landscape of nuclear deterrence, particularly in a region fraught with historical tensions, territorial disputes, and fragile crisis-management structures.

Common to these geographically distant conversations is the deepening unease about the reliability, stability, and manageability of nuclear weapons in a world shaped by technological entanglement and geopolitical fragmentation.

Nuclear weapons are not a new threat. But what stood out in both forums was the erosion of trust — in systems, in signals, in institutions, and in the ability of states to talk to one another when it matters most. The absence, distortion, and fragility of communication emerged as both a symptom and a cause of risk. And this risk is no longer confined to the familiar Cold War paradigms of missiles and megatonnage. It now emanates from code and clouds, satellites and servers, and from the strategic ambiguity that permeates the grey zones between peace and war.

Technological entanglement

Technological risks to nuclear stability are not new, either. Faulty computer chips, sensors, and backdoors, as well as worms like the Stuxnet, have long threatened nuclear systems. But today, rapidly changing digital technologies introduce new forms of uncertainty by creating fresh opportunities for malicious interference, systems failure, and misunderstanding.

Nuclear modernization exacerbates these risks by further enmeshing nuclear arsenals in a complex web of technologies, from cyber and space-based systems to artificial intelligence (AI) and quantum. At SIPRI, conversations focused on the unintended escalation of risk that can result. In Islamabad, we explored both the risks and the potential opportunities to improve safety, while acknowledging the glaring lack of governance mechanisms in place to shape these outcomes.

Taken together, these developments produce a reality in which nuclear stability, long a myth, is becoming a living nightmare, which can no longer be addressed in isolation. Today’s space-nuclear reality demands a cross-domain approach that recognizes the entanglement of technical systems, strategic perceptions, and geopolitical rivalries.

The crisis of communication: Fragile channels, growing dangers

If technological entanglement is the new context for nuclear risk, then communication — or its absence — is the critical fault line.

In both Stockholm and Islamabad, I repeatedly heard concerns about the shrinking space for dialogue, the brittleness of crisis communication channels, and growing opacity of military intentions and capabilities. We often assume that nuclear stability rests on deterrence, but deterrence itself relies on the ability to receive and send clear signals, to accurately interpret the behaviour of others, and to respond proportionally. When that level of understanding breaks down, so does stability.

During, the SIPRI workshop, I emphasized the need for resilient lines of communication that cut across technological risks and political divides. Resilience involves more than a reliance on hotlines or formal agreements. It’s about institutionalized habits of dialogue, shared frameworks for assessing risk and responding to crisis, and common vocabularies that help to avoid misinterpretation.

Yet as I noted in a recent policy brief, Geneva, We Have a Problem: Space Diplomacy Goes Nuclear, these habits are being lost — rapidly. The multilateral forums that once provided a foundation for space and nuclear diplomacy are stalling or becoming dangerously politicized. Meanwhile, the technologies we seek to govern are advancing rapidly, often under the control of actors who do not participate in the traditional arms-control circles.

What happens when a cyberattack disables a satellite relied upon for early warning, or when military AI misclassifies an action as hostile? In such a scenario, the time for interpretation is short — and becoming shorter. Without trusted mechanisms to clarify intent or de-escalate, we risk sliding into crises we cannot control — perhaps even losing the ability to understand and engage in real time.

Human by design

The conversations in Sweden and Pakistan reminded me that behind every technology, every system, every signal are people. History shows us that high-tech warfare is not more humane. Rather, it makes killing more efficient. From the trenches of Ukraine to the devastation in Gaza, we are seeing what happens when technical capability overwhelms human protections. We re-learn this same lesson every year on August 6 and 9 when we commemorate the anniversaries of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

War is a human activity. But so is peace. The most effective risk-reduction measures will be those that create space for human understanding, communication, and intervention — opportunities before systems are triggered, before signals are misread, before there is no more time.

Policy implications: Talking across divides

The risks discussed at the workshop and conference are not theoretical. Technological developments are shaping a security environment that is more fragmented, less transparent, and more prone to crisis escalation. The good news is that policy tools to reduce these risks already exist. The bad news is that we’re not using them with the urgency or scope that this moment demands.

One lesson that emerged clearly at both events is that effective risk reduction cannot remain the domain of only a few players. Crises are no longer confined to traditional theatres or controlled by great powers. In a world of shared vulnerabilities — especially in domains like space and cyber — the scope of participation in security governance must be stretched to include small and middle powers, technical experts, regional organizations, and civil society actors. All can help to shape norms, mediate tensions, and bridge political divides.

We must also think beyond deterrence and embrace the language and tools of crisis response. That means establishing trusted communication channels that can function under stress, investing in the information and platforms that can facilitate dialogue and shared understanding, and creating rapid-response networks that can intervene early in a crisis, especially when political channels are stalled or adversarial. Nongovernmental actors, in particular, can play critical roles in backchannel diplomacy, de-escalation, and trust-building.

If we are serious about crisis response, we need to invest not only in high-level diplomacy, but also in inclusive structures that can respond quickly, communicate clearly, and produce creative solutions. Future stability may depend as much on these networks as on treaties.

Published in The Ploughshares Monitor Summer 2025